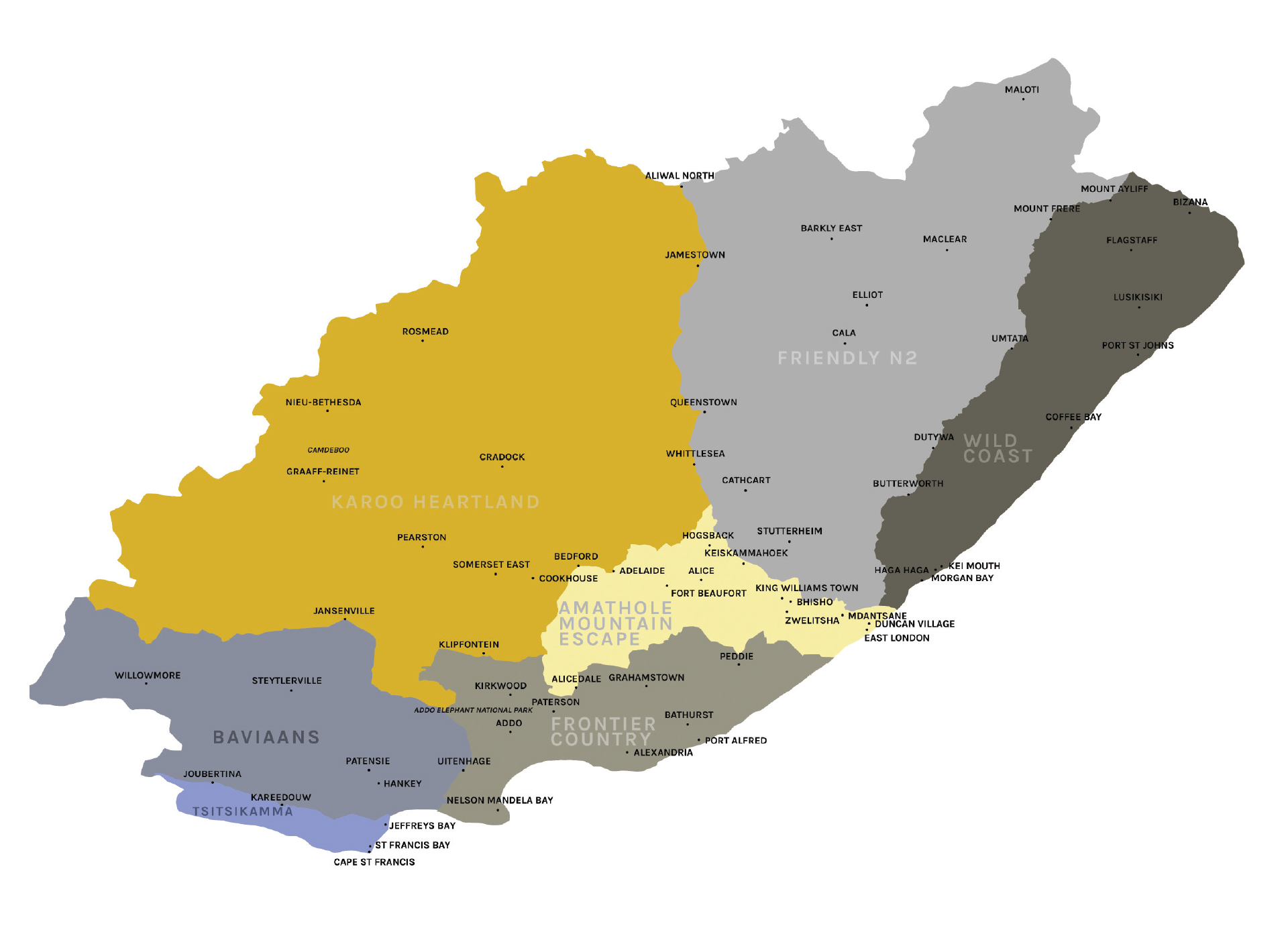

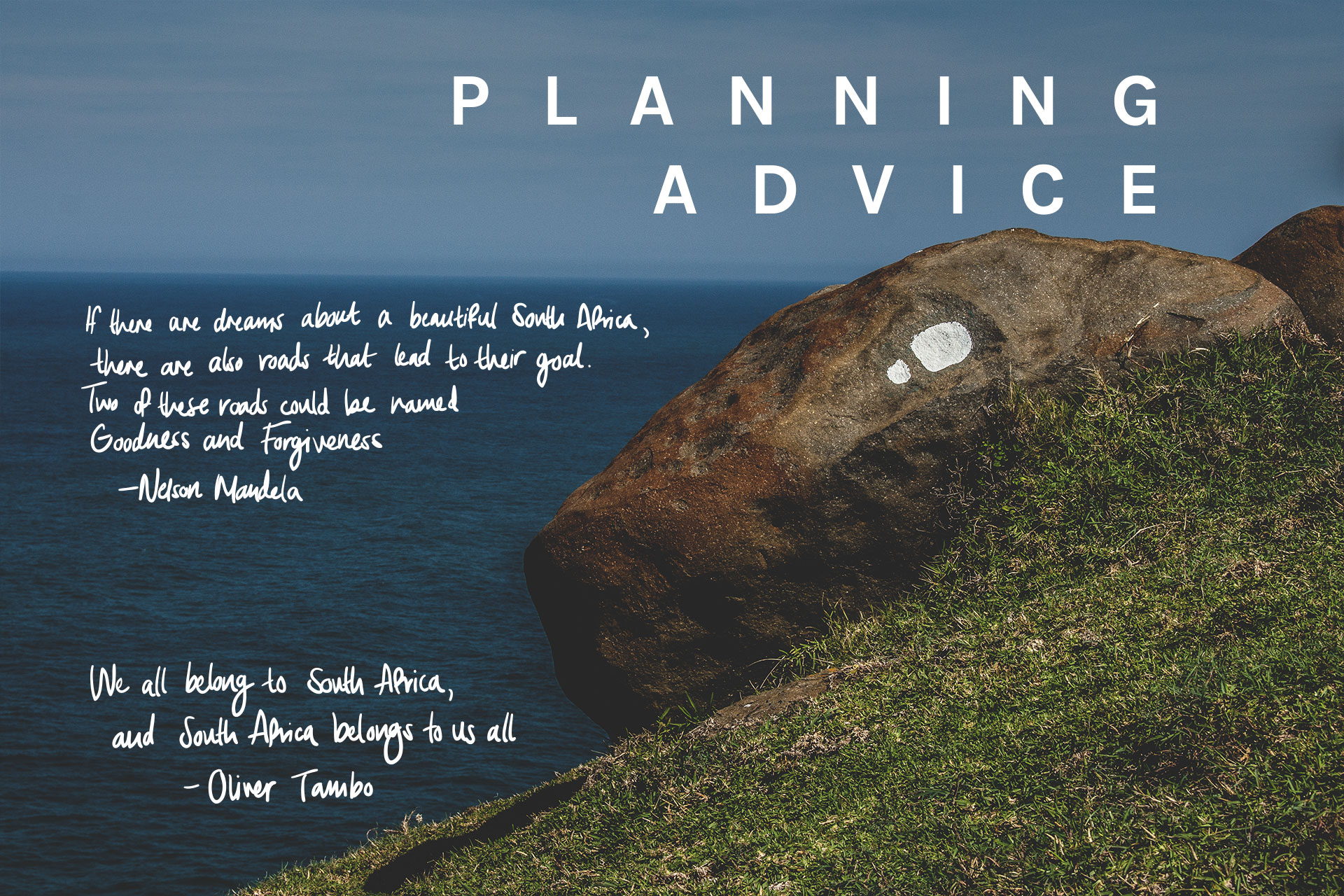

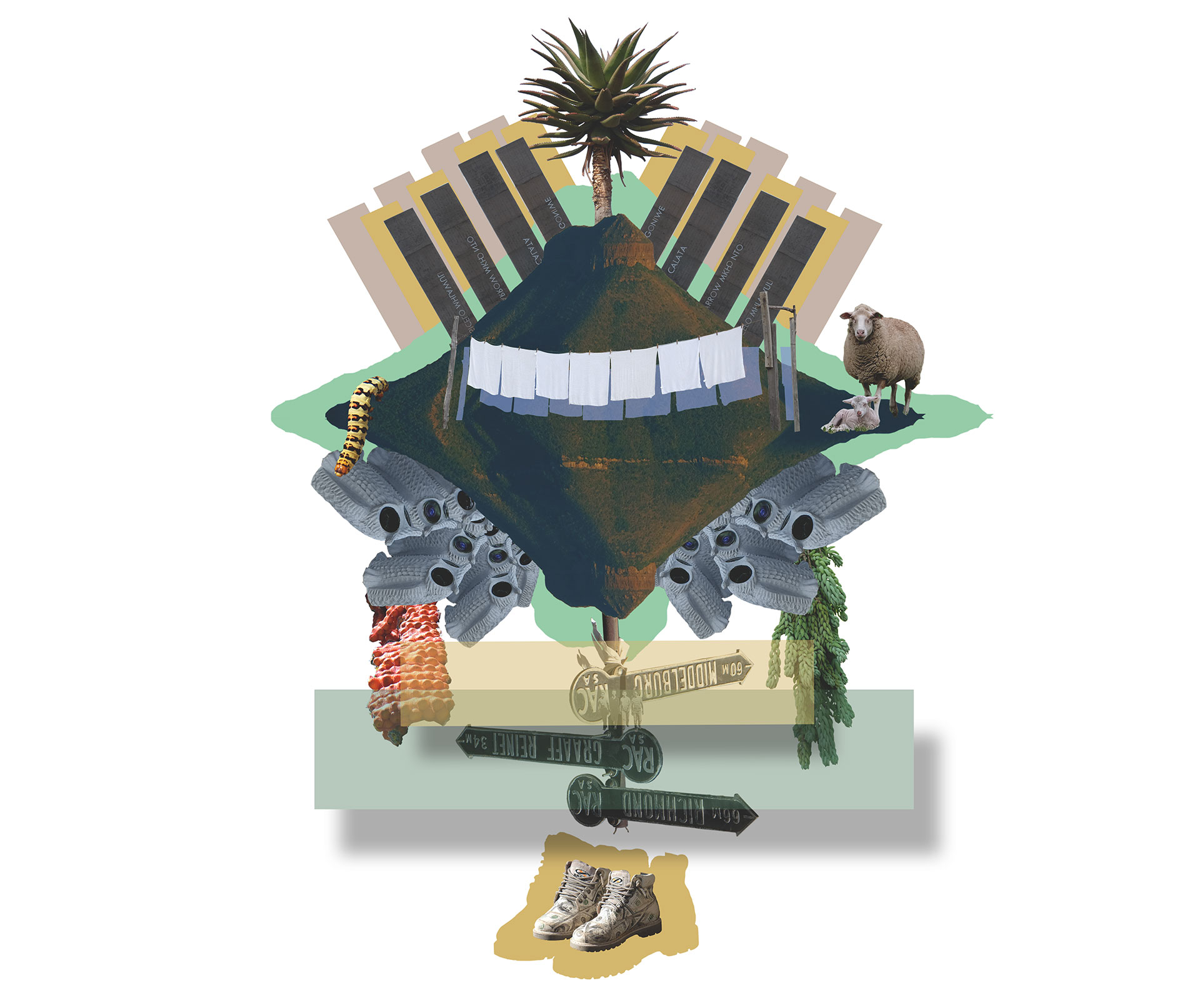

Over the past year, the Moments in Time Field Guide project has seen a team of ten travellers immerse themselves in a number of areas of the Eastern Cape. The experiences have left the travellers intrigued, energised and enriched by the engagements that have occurred – both planned and unplanned. The guide is an offering of all the interest and energy this project has generated, as well as an expression of the deep memory, the sense of nostalgia, combined with the excitement of new discovery that characterises the beautiful Eastern Cape. The team wishes to place it before you as a gift on your own journey of discovery and deepening engagement with spaces and places old and new.

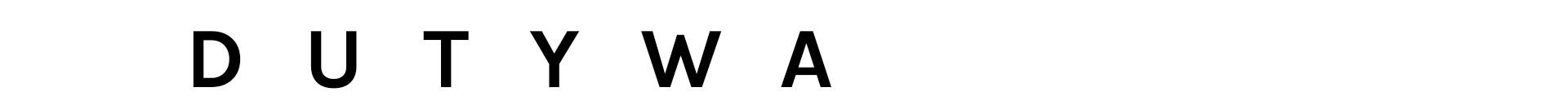

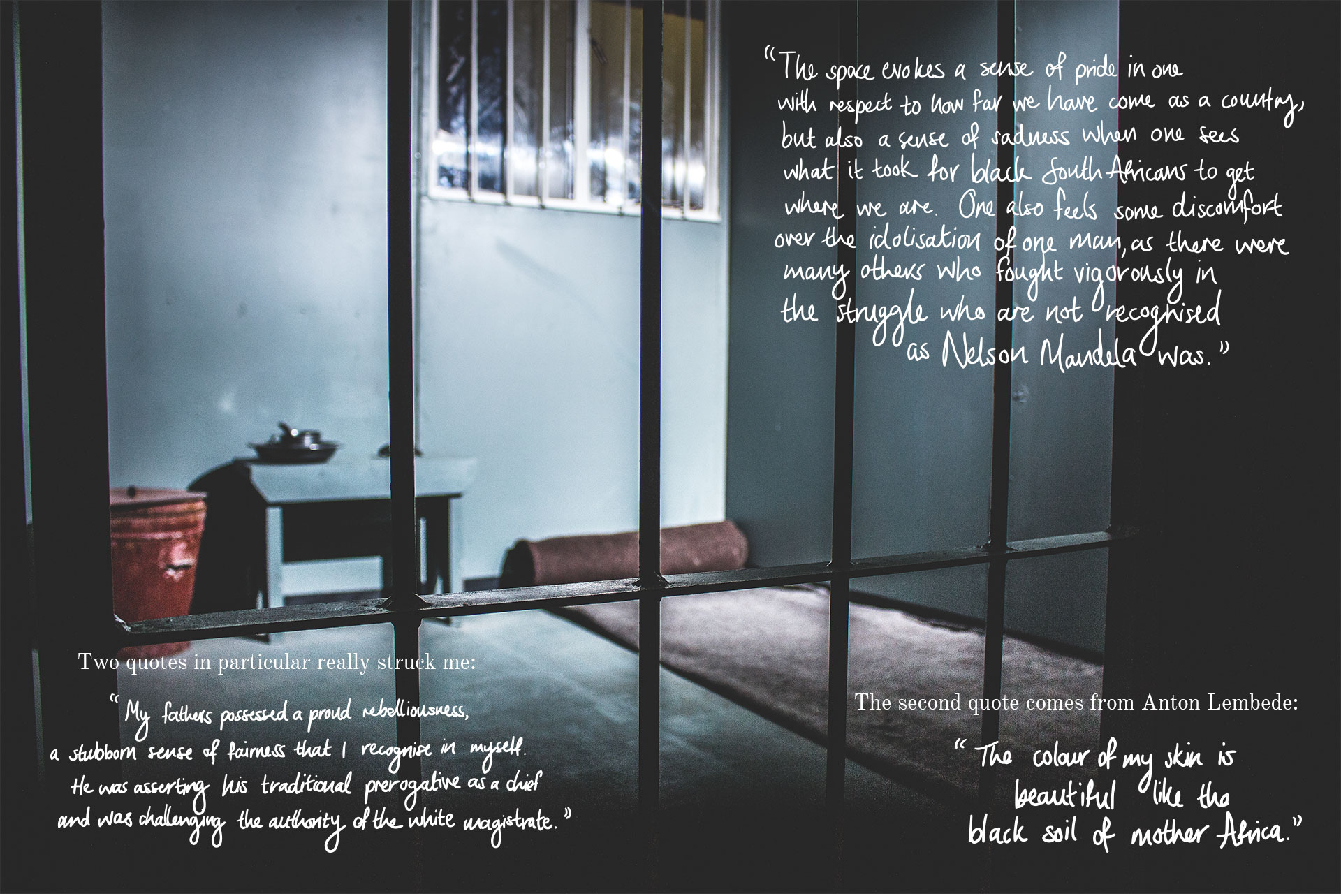

The notion of time providing a snapshot of a particular period is essential here. The periods that have led to this point play an important role in the development of the reality and the lived experience of communities. That lived experience is how the space of heritage relates to the individual at the time they engage with it. The different periods in time play a role in the way in which the viewer sees an area. The lenses through which the viewer, the traveller, sees the site, or the way in which they experience it, are relative given the context of the self.

The people involved from the Faculty of Arts bring with them different worldviews. Our crew of sociologists, anthropologists, political scientists, geographers, conflict analysts and psychologists allow for varying interpretations of the spaces and the experiences that go with them. The differing perspectives which distinguish each discipline, coupled with each individual’s socialization and own processes of understanding the world, makes for some unique representations. The ebb and flow of team performance was evident in who took the leader and follower roles in different settings, circumstances and even in response to different phenomena. This made for new discoveries that added richness to the narrative and the visuals.

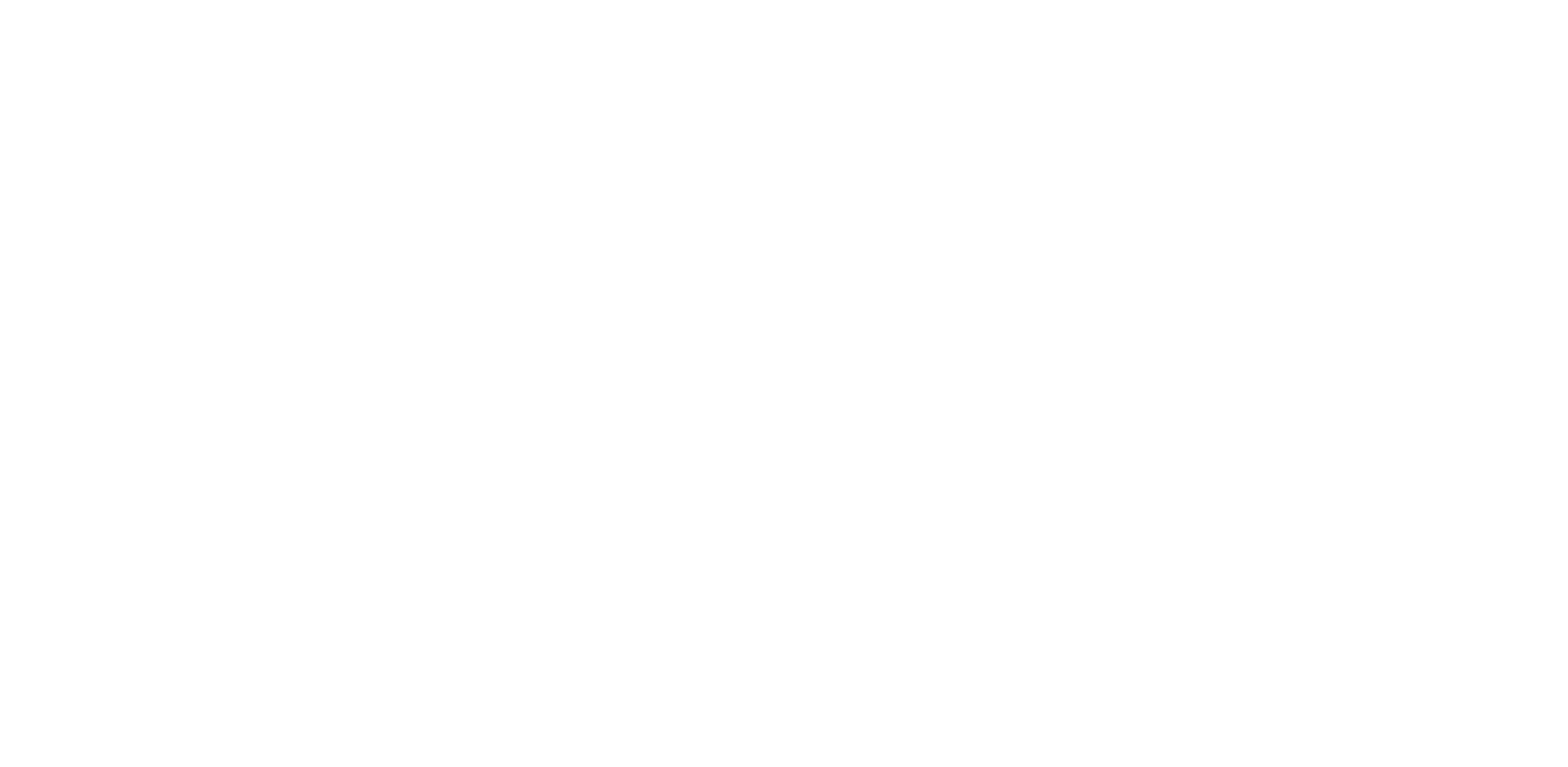

The field, which is vast and varied in appearance, culture, history and feeling, could be described as a colourful canvas wanting to be explored and even interrogated. This interrogation in the form of engagement with, and seeking an understanding of, the other, leads to learning about difference and, more importantly, similarity. Cultures are fluid and changing in the practices and rituals that play out over the years and this has been evident in the travels here documented.

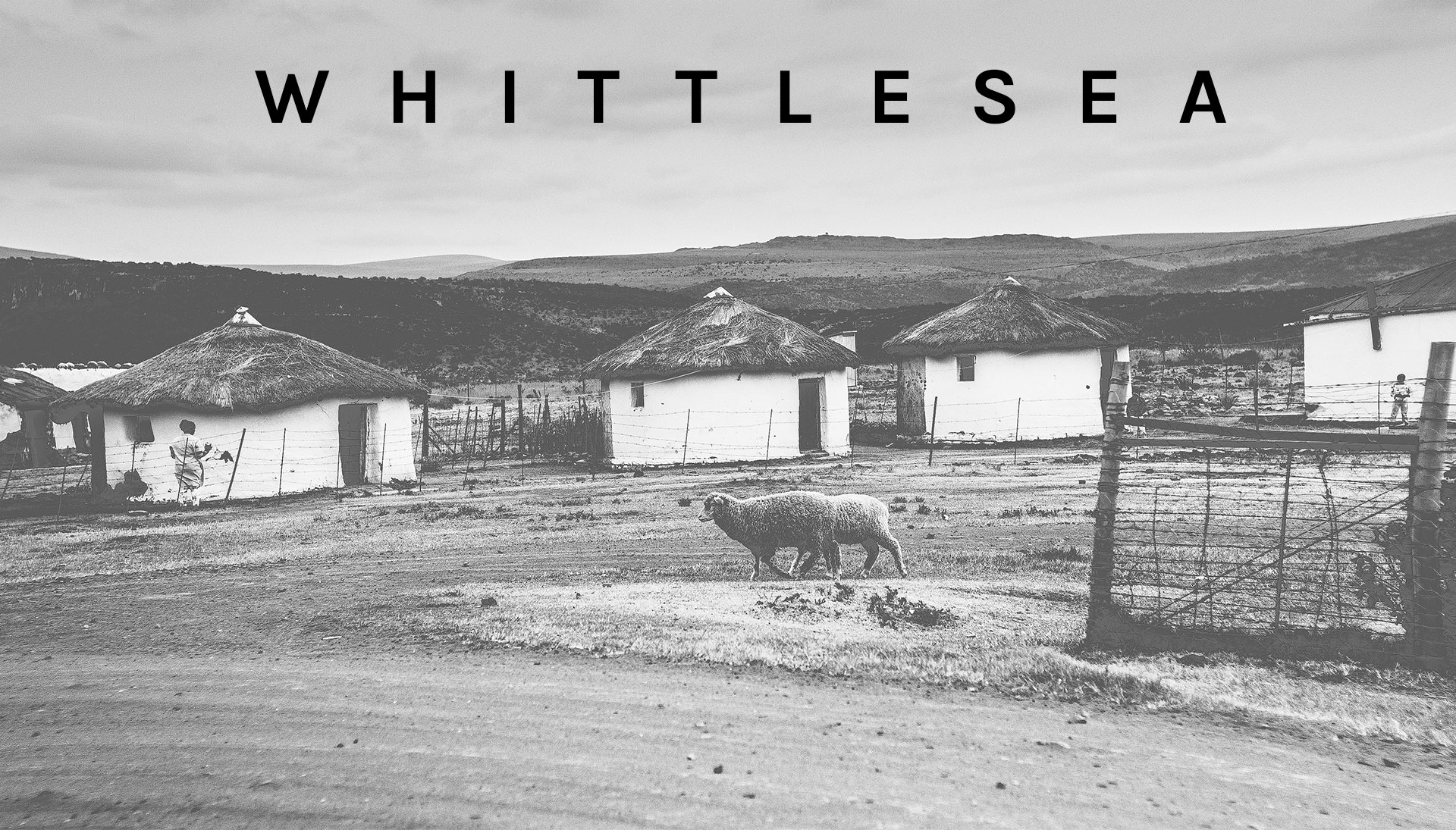

The journey we have embarked on has raised our interest in a number of different cultures. The sites and symbols of heritage evoked a reaction within each traveller. The mere point of memory is not enough, singularly, but it has to be engaged with. Merely, looking at it and passing by robs the experience from oneself and the site. The places of heritage must be allowed room for thought.

Through heritage, people are able to learn about culture, history and art. Culture is created by everyday living and the recognition of heritage brings to the surface ways of life as they once were. These heritage sites allow people to connect their own lives with that of the past. They draw attention to aspects of their lives and even enriches their lives. The process of reflecting on the site is important and through this, people are able to help shape not only their own thoughts but those of their communities.

Through this research project, we have learned about rich and diverse traditions and customs. To enable more people to gain access to such diversity, we need to engage them in making connections with the past and that which has occurred and holds significance to people. The exercise of partaking in learning about heritage itself enables communities to connect.

The team being from different disciplines caters for an interdisciplinary approach through greater team participation and increases the propensity for public duty and service. The stories of the different aspects of heritage are looked at from different views. The way the story could be told going forward promises to be more holistic. This approach fosters cultural diversity and aids social cohesion.

The team has experienced many highs and some real lows through the research journey. In certain spaces, we were informed that only one shade of visitor were welcome, shown books which present exclusionary leaders as heroes, and advised that places of worship were for designated groups only. We led the discussions that illicit good robust thought that made sense in the spaces we were in.

May the journeys of heritage and uncovering new thought from the old relics springboard that which becomes possible in society for the betterment of all.